Report: Bosnia and Herzegovina and the European Migration and Border Policy

Frachcollective has written a report on the current situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The collective supports People on the move (PoM) [1] with basic food, weather-appropriate clothing and sleeping bags, as well as wood for heating and cooking. Frachcollective has been on the ground in Bihać since late 2020. In this report the collectives describes the current situation of people seeking protection in Bosnia and Herzegovina and places it in the context of European migration and border policies.

Human rights violations at the external borders of the EU

At the beginning of October 2021, journalistic research teams (including from the ARD Studio Vienna, ARD magazine MONITOR, SPIEGEL and Lighthouse Reports) published video recordings – „Operation Korridor“: Recherchekooperation belegt schwere Misshandlungen von Flüchtenden an EU-Außengrenzen, Pressemeldung vom 06.10.2021 -in which, among other things, employees of the Croatian police can be seen beating refugees with batons and forcing them to cross the border out of the EU, thus providing video evidence of the already widely documented human rights violations at the Croatian EU external border. The Border Violence Monitoring Network(BVMN), an alliance of various organizations, has made it its mission to document pushbacks and the violence that accompanies them along the so-called Balkan route from Greece to Croatia to Italy. Between 2017 and 2020, the network has collected 892 cases of pushbacks with 12,654 people affected, making it clear that pushbacks are not isolated cases but a systematic practice to keep fleeing people out of the EU. The Danish Refugee Council (DRC) reported 16,000 illegal pushbacks from Croatia in 2020 alone, of which only 8.9% occurred without the use of force. In most of the documented cases, those affected reported brutal, inhumane violence and humiliation. Routinely, before people are sent back to Bosnia and Herzegovina, they are beaten with batons, fists, or stun guns. People return to Bihać with dog bites, injuries from kicks or metal bars; in addition, BVMN and DRC have documented cases of sexualized violence. In order to make another attempt to cross the border as difficult as possible for fleeing people, cell phones, money, but also clothes, shoes and sleeping bags are taken from them.

While in Bihać mainly people from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir and Bangladesh arrive, people from Turkey, Iran, Syria and North African states, among others, also flee via Bosnia and Herzegovina. Due to the upgrading of Europe’s external borders and illegal pushbacks, many people are stuck in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The EU thus abdicates its responsibility and leaves it to economically and politically dependent third countries to bear the social and societal challenges.

Bosnia and Herzegovina as a transit country

During the long summer of migration between 2015 and 2016, hundreds of thousands of people arrived via the so-called Balkan route, from Turkey and Greece via northern Macedonia to Serbia, and from there via Hungary and Croatia on to Austria and Germany. Bosnia and Herzegovina only developed into a frequently used transit country in 2018, partly due to increased militarization and control of the borders. In order to apply for asylum in an EU state, fleeing people in most cases only have the option of crossing the border by irregular means – pushbacks make this already difficult access to the asylum system even harder. Pushbacks are illegal practices and are a violation of the prohibition of collective expulsion and the non-refoulement principle, which are enshrined in both European and international law.

Picture: © frachcollective 2022

Picture: © frachcollective 2022

Political Situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina is marked by the Bosnian War, which took place less than 25 years ago, the disintegration of Yugoslavia, as well as political stagnation and economic difficulties. As a result, many young people are leaving Bosnia and Herzegovina to live in neighboring EU countries. Bosnia and Herzegovina itself has applied to join the EU.

The current political situation remains tense, especially when it comes to the constituent republic of Srpska and Serbia. Bosnia and Herzegovina is a multi-ethnic state, with a majority of people – just under 50% – being Bosniaks. Overall, about 30% of the population have a Serbian background and about 15% have a Croatian background. Milorad Dodik, a member of the presidency and head of the Serb-dominated entity Republika Srpska, is fomenting secession efforts, which have exacerbated the situation, especially in recent months, with plans to withdraw from state institutions. The politically fragile situation and fears of a renewed flare-up of violence are also reflected in society, where the memories and trauma of the Bosnian war of the 1990s are still present.

The Bosnian War, which began in April 1992, arose after a referendum proclaimed an independent “Bosnia and Herzegovina.” While a majority of Serbians living in Bosnia favored remaining in the Yugoslav state, numerous Bosnian-Serb politicians proclaimed a “Serbian republic”. The Bosnian Croats also sought a partition of the country. A war broke out that claimed more than 100,000 lives and displaced over 2 million people. Only after the public outcry and the genocide of Srebrenicabecame known, a forced peace agreementcome about, primarily through the mediation of the USA and the EU. It was formalized with the Dayton Peace Agreement. The Dayton Peace Agreement is an expression of the influence of Western power above all, because of its origins and the institutional foreign domination it contains. It regulated the division of the country into the entities of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska, decided with the aim of involving the warring parties linked to ethnicity. The result was a complex and paralyzed governmental apparatus with “more than 160 ministers, 3 presidents and, above all, the office of the High Representative, who, as a representative of the international community, has considerable power to dismiss ministers and pass laws (Bühlen, 2021). Since the first of August 2021 the office of the High Representative has been held by the German CSU politician Christian Schmidt, who specializes in security and migration policy issues. The complex political situation also has an impact on the situation of PoM. For example: The organization Medico International reported deportations without prior examination of the asylum status. In addition, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) runs so-called “voluntary” return programs but given the lack of access to the asylum process in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the violence and pushback at the EU’s external borders, there can be no question of voluntariness.

Official Camps and Restriction of the Rights of People on the Move

In Bosnia and Herzegovina there is not only a lack of access to protection and long-term prospects for people on the move, but also a lack of official care structures. Regionally, responsibility is shifted on from one place to another: Since the constituent republic of Srpska categorically refuses to take in PoM, most people are in Una-Sana Canton which borders Croatia. About 80% of the PoM in Bosnia & Herzegovina stay in Una-Sana Canton and from here they repeatedly start attempts to reach Italy via Croatia and Slovenia. In Una-Sana Canton PoM are mostly exposed to inhumane living conditions. In the official camps, financed by the EU, there is a lack of access to medical care, sufficient food and – as in the Lipa camp – access to drinking water and electricity. Some of the camps are nothing more than drafty overcrowded halls, tents or containers in which people are exposed to conflicts among themselves as well as arbitrariness and violence by employees of the security companies.

Lipa-Camp

Lipa is located 25 kilometres east of the city of Bihać in a secluded, largely unpopulated area. The isolated location of the camp makes it clear that People on the Move are deliberately being pushed out of the public eye in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In addition, people seeking protection are massively restricted in their freedom of movement and excluded from public life, as they are largely denied the use of public transportation and shopping facilities as well as the right to assemble in public places.

Originally planned as a temporary shelter, the situation in Lipa came to a head in September 2020, when local authorities decided to close Camp Bira in Bihać and move the PoM living there to Camp Lipa. At that time, the Lipa camp was already overcrowded and lacked sufficient drinking water and electricity. As a result, 2000 people lived in a camp designed for about 1500 people. Accordingly, the conditions can be described as catastrophic: Several people had to sleep partly in one bed with one blanket, all in large tents. There was no hot water and only five showers. Due to the cramped quarters and the hygienically inadequate conditions, people were unable to protect themselves against diseases such as scabies. It is not uncommon for PoM to have severely infected wounds that had to be treated with antibiotics. Time and again, organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Blindspots have pointed out the lack of proper and winterized care in the so-called reception centers, such as Lipa. Although people are particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic, improvements in sanitary and medical conditions have been needed for a long time. Briefly, in December 2020, media attention focused on the situation of refugees at Bosnia’s external EU border when the tents of Lipa Camp burned down, and the then fully homeless people held out for days in the snow-covered remains. Representatives of the EU merely admonished Bosnia and Herzegovina to “manage migration better” and blamed the humanitarian catastrophe on the failure of Bosnian authorities, instead of reflecting on its own role in the inhumane system of closed borders and violent pushbacks. A reopening of Lipa Camp was “celebrated” on November 19, 2021. For weeks this date was postponed due to construction works. The connection of the electricity network was still not completed at the opening.

Picture: © frachcollective 2022

Picture: © frachcollective 2022

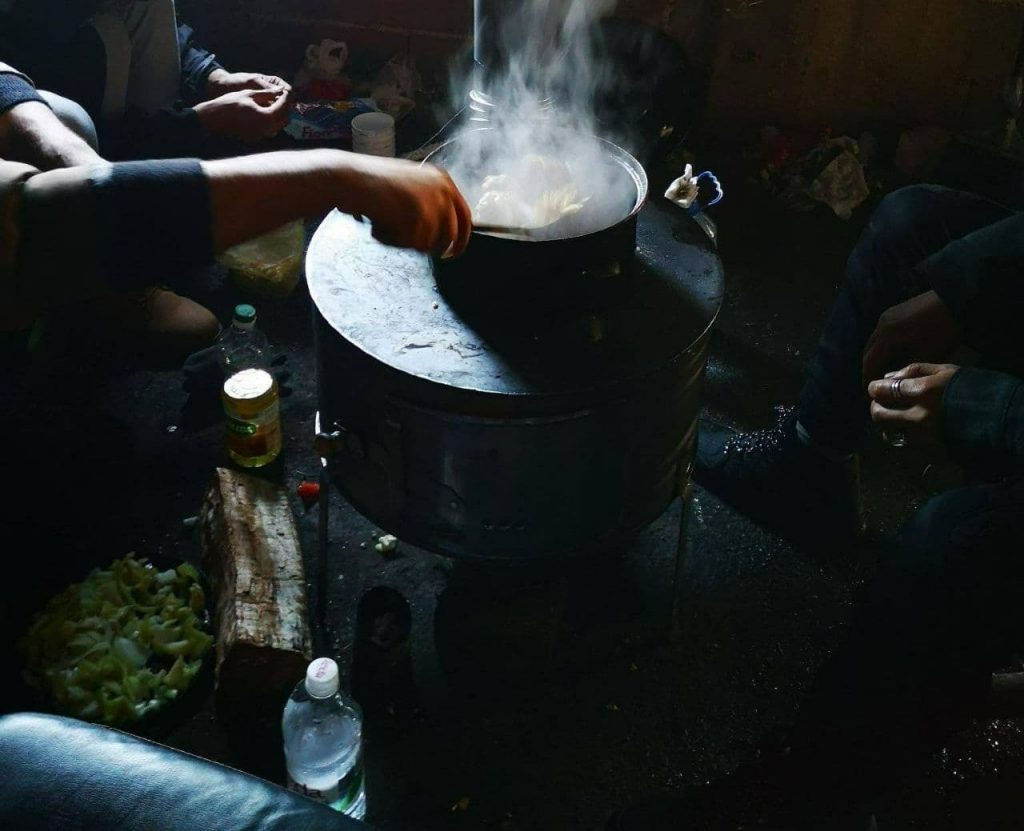

Self-organized (unofficial) squats

Due to the disastrous conditions in official camps, but also the desire for self-determination, many PoM live in so-called squats [2]. These are often located in abandoned houses, ruins of buildings or in tents in the so-called Jungles [3]. Without electricity, heating, sanitary facilities and with only very limited access to water, the PoM live in self-erected tents and camps, mostly built from plastic sheets. Surrounding rivers and lakes often provide the only permanent access to water, which is used for drinking as well as cooking and washing. The water is often polluted, posing a high health risk. People often complain of digestive, kidney, muscle and joint problems. The long-term health consequences of this are not yet foreseeable. Access to health care in hospitals or doctors’ offices remains denied to People on the Move. The support and care of the people in squats is therefore mostly provided by volunteers and large humanitarian organizations. However, due to the criminalization of solidarity-based aid structures, adequate support is not sufficiently possible.

In addition, People on the Move are exposed to great reprisals even in unofficial structures. In the summer months of 2021, evictions [4] repeatedly took place on a weekly basis. The rights of freedom of movement and self-determination are thus systematically attacked. The evictions are carried out by Bosnian police and security forces. In the summer months, they arrived in the early morning hours and forced squat residents who could not hide in time to move to Lipa Camp by bus. People’s personal belongings are then burned or disposed of in the garbage. The evacuated buildings where people had been living are barred, cordoned off and regularly patrolled to prevent people seeking protection from moving back in. However, shortly after the forced transfer to Lipa, many PoM made their way back to Bihać on foot – in snow, scorching heat or rain. Having self-determination and a certain “freedom” seems more important to many than the “benefits” of the camps. Unfortunately, the way back to Bihać is also often marked by violence. Occasionally, special forces wait outside the city to forcibly dissuade people from returning to Bihać.

Criminalization of solidarity support work

The regular evictions of unofficial camps and squats also pose challenges to solidarity support organizations. The criminalization of solidarity structures makes the work with People on the Move enormously difficult because the repression by the Bosnian police can be felt on a daily basis. People who show solidarity with people on the move are increasingly affected by controls and intimidation attempts by the authorities. While people with EU passports are only expelled from the country, the risks for Bosnian people, also on a social level, are much more far-reaching. Police presence is particularly high on eviction days. Criminalization serves as a key instrument of intimidation to prevent support for People on the Move.

Consequently, when food and NFIs (non-food-items) [5] are distributed, the atmosphere is often one of caution and uncertainty. Food distribution is supposed to go quickly because the car carrying the food could be discovered. This leads to a lack of important time for interpersonal contact. Repression and insecurity are always present, even when it is just a matter of being seen with PoM, such as during a simple conversation or a walk.

Picture: © frachcollective 2022

Picture: © frachcollective 2022

EU funding of (Bosnian) border practices

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s border policies are supported with funds from the EU: Since 2015 the EU has provided around 90 million euros for the development of infrastructure and emergency shelters for PoM. The goal is to strengthen migration and border management in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This means outsourcing responsibility for the care of protection seekers from the EU to Bosnia and Herzegovina and results in more people being housed in camps under inhumane conditions and being violently prevented from crossing EU borders.

Some of the support money went to aid organizations such as Save the Children and the Danish Refugee Council. However, the bulk of the money went to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Bosnia and Herzegovina: since June 2018, the organization has received a total of 76.8 million euros, which was used to fund the Lipa Camp, among other projects This money was also intended to provide support to protection seekers in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Covid 19 pandemic. However, in view of the overcrowded camps, spatial confinement, bunk beds and lack of medical care, it is doubtful whether these funds were used to improve care for the people on the ground. State institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina have received 3.4 million euros for new vehicles, drones, thermal imaging cameras, and heavy protective equipment, which can be used to monitor PoM and clear unofficial squats, among other things. However, the exact breakdown of the use of the funds is not available at the moment.

The EU not only contributes financial resources to the establishment of camps and monitoring structures but also donates equipment. In July 2021 the Bosnian border police received vehicles worth about 1.5 million euros and the state investigation agency SIPA received equipment worth 230,000 euros. Already in 2019, Bosnia and Herzegovina received new vehicles worth 124,000 euros.

Financial assistance can be a way to support states. It can be a way to create new social perspective. But it is mainly European arms companies that are earning money from this militarization of European border policy. For the period from 2021 to 2027 the EU Commission also wants to provide another 8 billion euros to support states in expanding border security. The border protection agency Frontex was most recently promised a budget of 5.6 billion euros until 2027. This money could also be invested in schools and hospitals, which are important for the basic care of the local population as well as PoM.

We don’t want to look away and neither should you!

The result of the current European migration and border policy is a dead end, where freedom of movement is more and more restricted, and people are systematically oppressed and deprived of their basic rights.

What can you do?

Draw attention to the situation!

You don’t have to go to Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Greece or other regions to show solidarity.

Inform yourselves and discuss with each other!

Question the system in which we find ourselves. Question the European asylum policy. Question and be critical. This is a central point that is too often underestimated.

Try to build up pressure on the government together with other people!

Look for associations or collectives in your area with which you can become active. Start actions or financially support organizations at the EU’s external borders. Raise your voice!

Want to learn more about this topic?

Then check out this webinar by BalkanBrücke: “Support work, voluntourism and international presence in Bosnia and Herzegovina . Between Political Responsibility and Historical Continuity.”

[1] People on the move (PoM) – is an overarching term that encompasses all people who also fall under the categories of refugees, asylum seekers, protection seekers, migrating people etc. The term focuses that these people are individuals and emphasises that people are on the move, have a goal and want to continue their journey.

[2] Squats – self-organised places where People on the Move stay

[3] Jungle – a space away from the city; usually denotes woods or undergrowth

[4] Eviction – Evictions of self-organised squats

[5] NFI – (non-food-items) needed goods such as clothing, tents, sleeping bags, firewood (with the exception of food)