Voluntourism

What does voluntourism actually mean?

A phenomenon with a high appeal in international volunteering is the so-called voluntourism. It describes a combination of “volunteering” and “tourism”, with the latter being the focus.

- Voluntourism is made possible and advertised under slogans such as “travel and help”, mostly by agencies that promote volunteering as part of an exciting trip and as an adventure.

- The volunteers’ suitability to work in the project is less important here than their financial possibilities. Volunteers often pay large sums of money to participate in these programmes. In most cases, however, the money goes mainly to the agencies instead of the projects on site.

- Even very short activities of volunteers, embedded in a larger trip, can be understood as voluntourism. Because most projects require a certain period of familiarisation and thematic engagement with the project objective, the projects can rarely have a sustainable benefit from short-term, more casual support.

The benefits of this volunteering are enjoyed only by the volunteers themselves: they experience an international and intercultural “adventure”, make new acquaintances and friends, can usually use the experiences for their CVs and conclude their stay with the feeling of having done “something good”, regardless of the reality.

Often, it is difficult for local organisations, that host volunteers, to openly criticise the situation as they might be dependent on contracts with the agencies or financially on the volunteers.

Certainly, many volunteers have good intentions and really want to help through their commitment. But of course, the success and impact of social projects in countries of the Global South is not based on the work of volunteers from Western countries who are flown in from abroad for a short period of time or make a detour during their holidays to provide support with their limited skills.

For many people in the host countries or in the projects, this form of volunteering is often more harmful than anything else. One example is volunteering for a few weeks or months in orphanages and the structures this creates. The organisation ReThink ORPHANAGES points out that the high demand for projects in orphanages means that children are actively recruited to fill places in orphanages and can thus be separated from their families. In addition, children’s rights and protection can be neglected in these projects: Some organisations do not require a criminal record check as is usually the case when working with children, and the repeated turnover of volunteers can contribute to the development of attachment disorders in children. Similar criticisms can be made especially when working with children in refugee camps. If the work with vulnerable groups is at the centre of a project, volunteers should always question whether their own qualifications are sufficient for the work in question, whether the rights of the people are respected and whether the usually short stay really contributes to an added value for the project and the people it is supposed to support. Especially the latter involves a critical reflection on one’s own motivation and effectiveness in the projects.

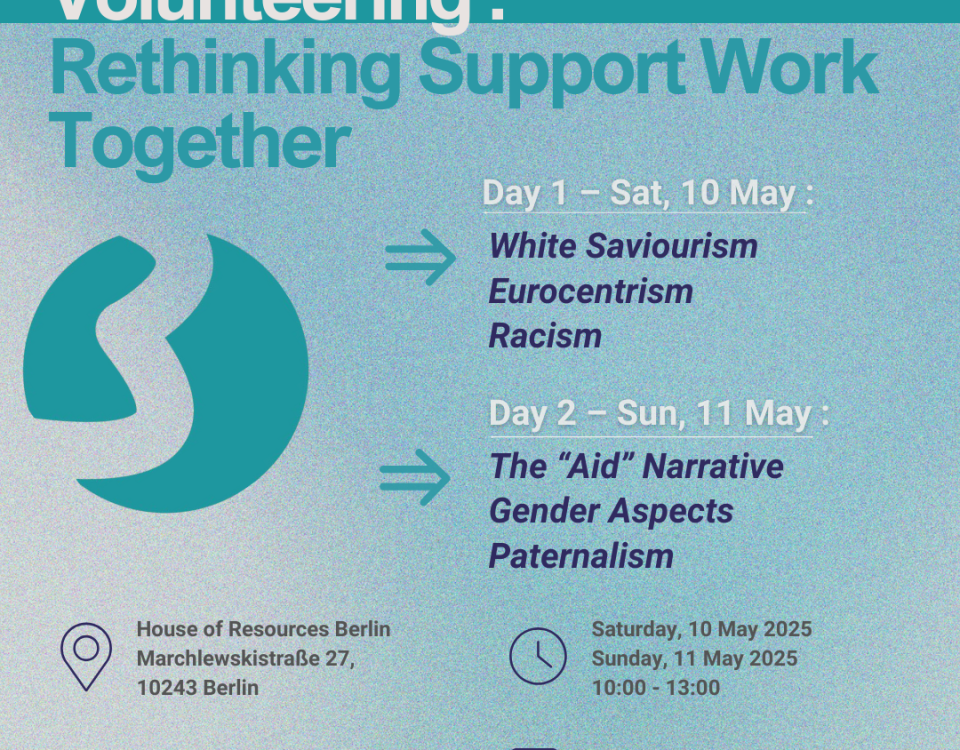

How can you avoid voluntourism structures?

Look carefully when choosing your organisation:

Does it fulfil a certain level of critical self-reflection and pay attention to sustainability? Social projects usually want to fill a gap in the system or bridge a certain emergency in the long term. But if projects do not last long or make promises they do not keep, they can do a lot of damage or leave an even bigger gap. For example, are problematic political structures being reproduced by the project, or does it aim to change them? This is why in many places the overriding guiding principle of humanitarian aid is rightly: Do no harm!

Will your trip really help the community or the local people?

Take the time to check whether your planned volunteering trip will actually help the local community or even harm it in the short or long term. In order to actually help solve certain social problems, financial support for a project you have chosen is often at least as useful as investing the money in the trip. Otherwise, in many places, a substantive discussion of the issue and subsequent advocacy (for example, through talks, petitions, campaigns or the like) at home can also be in the spirit of your intended outcome.

For all those who want to learn more about voluntourism, we can recommend theTED Talk by Hannah Ward. From minute 4:55 onwards she talks about ethical volunteering and voluntourism.